Too Lazy to “Type”

Are we really writing “dynamic” programs, or are we just trying to avoid writing down all those type signatures?

I’m currently doing research for a survey on [program] verification and testing in dynamic languages in order to find out what information is out there about verifying program correctness in languages like JavaScript, Python, and Ruby. I’ve made a few discoveries. If you saw me tweeting the following, you saw what I discovered:

It’s not so much a discovery as a confirmation of some of the views I’ve had about Ruby programs for a while. Many Rubyists tend to believe that they use Ruby because it’s dynamic, and “dynamic” apparently means “you can do things you can’t do in Java”. In a syntactic sense, this is certainly true, but are our programs really “dynamic” in the sense that they change “at runtime”? Or is it more accurate to say that we’re simply performing what Java programmers call “code generation”—at “load time” instead of “compile time”? And what about dynamic typing? Are we really passing in wildly arbitrary ever-changing types to methods, or maybe the truth is we’re just too lazy to add type annotations to our code and using Ruby gives us an excuse to be lazy.

First let me point out that I certainly don’t believe that we’re just doing dynamic code-generation, or that we’re just too lazy to add type information, but perhaps there’s a little bit more truth to it than people want to admit.

Undynamifying the Dynamicity of our Dynamic Dynamo

The paper I linked above, available here from the Diamondback Ruby guys entitled “Profile-Guided Static Typing for Dynamic Scripting Languages”, looks at a way to automatically infer type information by “profiling” your program (at run-time), looking for all the dynamic patterns, and, for the most part, translating them into their static equivalents. Yep, I said it. Static equivalents. Believe it or not, their results show that many of these “dynamic” programs can in fact be translated into fairly static ones just by unrolling a lot of the meta-magic that we take for granted. The paper looks at some constructs such as the following example from ‘net/https’, and explains how we’re really not doing anything dynamic at all:

def self.ssl_context_accessor(name)

HTTP.module eval(<<End, FILE , LINE + 1)

def #{name}() ... end # defines get method

def #{name}=(val) ... end # defines set method

End

end

ssl_context_accessor :key

ssl_context_accessor :cert_store

It’s easy to see that this code is executed immediately at load time. Although it’s possible for someone to generate a method at run-time (by run-time I mean much later after the initial .rb file was require‘d), it’s a fairly rare occurrence. What we’re really doing here is just avoiding to extra LoC involved in typing out those def’s each time. What we’re doing here really is just runtime code generation. By the way, yes, this is just a fancy attr_accessor.

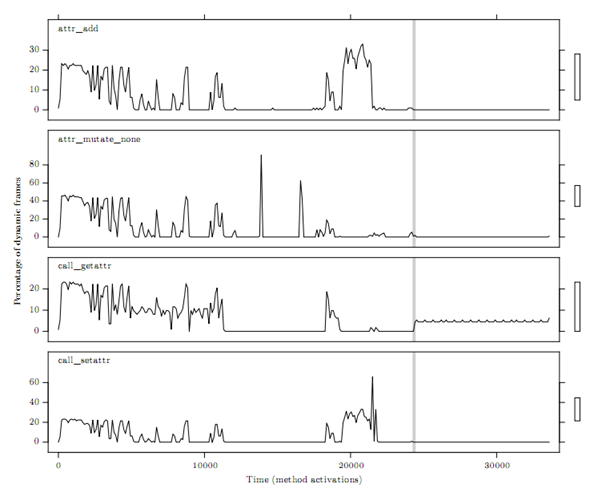

Another fairly interesting paper titled “Evaluating the dynamic behaviour of Python applications”, shows that programs in dynamic languages with these runtime modification behaviours often stop modifying their behaviour after a certain amount of “load time”.

Granted, this is Python, not Ruby, but I’d bet you’d find very similar results in Ruby as well. Another fairly well cited article titled “Aggressive Type Inference“, also targeting Python, comes to the same conclusion that we don’t really write such dynamic programs after all.

What About Types?

Until now I’ve been talking about Ruby as a “dynamic” language, but not a “dynamically typed” language (there’s a difference, and it’s in the “type” part). Of course, the article title is about typing, so let me touch on that subject.

The reason I talked about eval() and its dynamically natured friends until now is that, without these dynamic features, type inference in Ruby would be a lot easier. Ironically enough, it’s actually easier to implement a completely dynamically typed language if it does not support dynamic functionality like eval()—that is to say, it is easier to perform type inference on a typeless Java program than a typeless Ruby program. Mirah, Charlie Nutter’s static variant of Ruby basically proves that this is possible with very little modification to existing Ruby programs. In this sense, without all this meta-magic, we would be able to have fairly complete static typing in Ruby.

Of course, this is not universally true, and there are plenty of Ruby programs that are based heavily on structural typing (or duck typing) rather than class based OO-style typing. However, these programs, just like above, are often not structurally typed by necessity, but by DRY simplicity.

Consider every Rack middleware ever: none of them inherit any superclass, and yet we can “#use” them just fine. Instead, they all just simply implement #call. What we really have is a protocol, or interface, depending on your terminology. There is no reason you could not enforce some superclass or at least inheritance through a mixin that had a “call” method. That difference would simply change:

class MyMiddleware

def call(app) ... end

end

To:

class MyMiddleware

include Callable

def call(app) ... end

end

Lambdas, would of course also “include Callable”, just to keep the type system sane. This example makes up a really large number of use cases, from my own personal experience. So, when someone says they’re using a dynamically typed language because it’s easier to implement things like Rack, what they’re really saying they just don’t want to write this stuff down for the compiler—usually forgetting the fact that they still have to write it down anyway, for the user. Remember that your middleware will still fail if you don’t implement #call, and this protocol is actually fairly well defined in the Rack specification (and verified by Rack::Lint), so it’s not like type information is completely omitted. If anything, the laziness of not defining the interface up front in the program itself makes it more difficult to express the type information later, but that’s more of a discussion on documentation.

Again, this is not universally applicable, and I bet there are a few edge cases, but ask yourself: how often do you write Ruby code that can really not have some kind of class based inheritance type system? For me, I can’t think of many cases. How often do you pass arbitrary types to methods without at least having a well-defined set of types that can be accepted by the method? The worst it gets for me is a case switch for a handful of types, but that’s just because Ruby does not support overloading. In a static language, I wouldn’t need to have a single method support multiple types, I’d just overload it.

I’d really love to see some research on case studies of how often arbitrary structural typing (that cannot be refactored into polymorphic relationships) is really used in dynamically typed languages. If anyone knows of any research/papers in this field, I’d love to hear about it.

I'm Loren Segal, a programmer, Rubyist, author of

I'm Loren Segal, a programmer, Rubyist, author of